Masahiro Maeda (Kanazawa Seiryo University)

1 What is Dictogloss?

Dictogloss is a communicative activity in which a teacher reads aloud a short story with coherent content several times while learners take notes on only key words, and then they collaborate with other learners to restore the passages to a level of content and structure equivalent to the original story. Dictogloss is a method of language teaching based on the traditional dictation technique proposed by Wajnryb (1990). Her book, “Grammar Dictation” (Oxford University Press) is well known. She describes the detailed steps of dictogloss in five stages, which can be summarized as follows (p.7).

| (a) A short, dense text is read (twice) to the learners at normal speed. (b) As it is being read, the learners jot down familiar words and phrases. (c)Working in small groups, the leaners strive to reconstruct a version of the text from their shared resources. (d)Each group of students produces its own reconstructed version, aiming at grammatical accuracy and textual cohesion but not at replicating the original text. (e)The various versions are analyzed and compared, and the students refine their own texts in light of shared scrutiny and discussion. |

As the title of her book suggests, Dictogloss, also called “grammar dictation,” is aimed at mastering the target grammar. Her method was designed for first language acquisition (L1) and needed to be improved and revised for Japanese learners of English as a foreign language (EFL). Therefore, Maeda (2008) proposed the more educational ways of Dictogloss for learners in EFL environment. He referred to the listening chances, the speed of reading aloud, and whether the materials are first look or already learned. These are particularly important elements in dictogloss for EFL learners but have not been discussed so much based on the practical experiments in dictogloss research. The procedure of the dictogloss for EFL leaners by Maeda is summarized as follows.

| (a) A short, dense (already-learned) text is read (three times) to the learners at speed of 140 / wpm. (b) In the first listening, learners just listen to the story without doing anything to grasp the whole story. (c) As it is being read in the second and third time, the learners jot down familiar words and phrases that they regard as important. (d) Working in small groups, the leaners strive to reconstruct a version of the text from their shared resources. (e) Each group of students produces its own reconstructed version, aiming at textual cohesion and the appropriateness of situation but not at replicating the original text. (f) One more chance to listen to the story is given for learners to fill the gap between their “holes” in making the story and the original story. (g) The various versions are analyzed and compared, and the students refine their own texts considering shared scrutiny and discussion. (h) In addition to shared scrutiny and discussion in the previous step, writing the shirt comment about what learners found and noticed through dictogloss is required. |

2 Procedure of Dictogloss

English learners may have experienced at least once when their friends ask them to speak something in English. They may find that it is difficult to produce output without any topic or input. Learners of English produce output by having some kind of topic or input, by using their background awareness and existing knowledge of the topic, and by selecting and reconstructing information from the input. Dictogloss is an activity which starts with listening to a story with a specific topic as input. Then learners take notes only on what they need to know and collaborate with their peers who have brought their notes to reconstruct the original English text by using their background awareness and pre-existing knowledge.

In everyday life, based on notes we took, or what we memorized as some keywords in our mind during listening to something such as lessons at school, meetings, or daily conversation, we sometimes restore or rebuild the story later. For example, we often take notes while talking on the phone in everyday life. Based on the notes, we remember what we talked about and sometimes we talk about it to others. These are behaviors that we do naturally in our daily lives and are communication that we do in real life, or behaviors that lead to communication.

Regarding a text used in dictogloss, “content-experienced” English texts that learners have already understand the contents to some extent is recommended for dictogloss. In everyday English classes, the English textbooks authorized by MEXT (the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology) is supposed to be used in Japan. Most of the authorized textbooks have summaries of the story in each unit. Using the summary of the unit story is the best way to do dictogloss practice. This will reduce the burden on learners to simultaneously process content and linguistic form (grammar and word form), and it also demonstrates the “focus-on-form” effect of linking content and linguistic form.

Teachers should use the stories in the authorized English textbooks repeatedly changing the aim such as having learners grab the outlines or understand the detailed parts and so on. Maeda (2012) proposed the “Colander to Tray Model (CTM),” in which students are mainly taught focusing on the outline and emphasizing “awareness at first” In this stage, only the big information remains in the net of colander, while other small information slips through the net of colander. Then, step by step, they are taught grasping on the detailed part and almost all the information would be received on a tray without missing anything. This model begins with brainstorming using unit titles and pictures, and then leads to text instruction through interactive listening (or teacher aural interaction) that deals with the content rather than a CD reading of the text. Students read the story silently in class for the first time (without any preparation as homework), and the teacher’s first question should be something like “Is it a good story? Are you interested in this story? “What is this story about?” that would make learners imagination broaden. Then, learners have an interaction in pairs as a collaborative learning to share the content of what they read. After this collaborative learning, a teacher asks some questions in which all students can easily participate, such as True / False, and then begin the second silent reading. Then, the third silent reading is done with 5W1H-Questions to “get the details” and questions to elicit inferences. Students are made to read the same English sentence two or three times repeatedly with different purposes. Since diversity of ideas by each learner can be expected in this stage, interactive and deep learning should be done. What is more, teachers should give learners plenty of reading aloud opportunities after leaners grab the contents. Dictogloss activity would come after these instruction and procedures are done. The following is the detailed explanation of Dictogloss proposed by Maeda (2008).

[Step (a)~(c)] The standard number of listening is three times, with the first listening being done without taking notes, and the second and third listening being taken as notes. This is called “global listening,” in which the goal is to first hear the outline and main points of the story, and the process is for students to decide for themselves what they should hear. It is to focus on and understand the necessary information rather than trying to listen comprehensively to everything, as stated in the new guidelines for upper secondary school learning. In general, this will encourage top-down processing by the learners.

[Step (d)~(f)] In the process of bringing in their own notes and restoring the original English text, students teach each other, and learners can become “teachers” of each other. By instructing students to “focus on grammatical correctness and coherence of speech, but not necessarily the original text itself,” learners begin to discuss their ideas with each other, saying, “This is what it should mean here,” or “This is the kind of English that should come here. If the learners are asked to reconstruct accurately as same as the original English sentence,” they will only discuss the agreement between the original and the restored sentences, and they will think only in terms of correct/incorrect answers.

When the audio is played again at the right moment, the classroom, which had been a place of lively discussion, instantly becomes a space of silence, and the learners’ concentration is suddenly heightened. The learners’ concentration at this point was so strong that they were really listening to English with such concentration that they fell forward. This is called selective listening. This is called selective listening. In this selective listening, the learner focuses on the necessary information and only listens to the information that is necessary for the task and does not have to listen to the parts that are not necessary.

[Step (g)] Teachers distribute the original text, have students compare and analyze it with the restored English text. After this, students will summarize their findings and feelings by writing them down. The reason the term “analyze” is used here rather than “check” is that we do not want students just to match their writing with the original text in terms of the linguistic forms. One of the groups restored the English sentence like “Why don’t you try a raw egg tomorrow?” in the author’s practice. The original sentence was “Why don’t you try one tomorrow?” In the space for what students noticed after dictogloss practice, one of the students in the group wrote, “I thought that the words “raw egg” should definitely come here, considering the meaning.” However, the student said, “I realized that I could replace it with “one” as pronoun.” In many classes, the pronoun “one” would be shown first, and then the students would be asked by their teacher, “What does this “one” mean? And the teacher will explain “the answer.” However, in this dictogloss practice, the learners, through the power of their own discussion, were able to map a semantically compatible word from the context and discovered that it could be replaced by the pronoun “one, “forming the function and concept of the pronoun “one.”

[Step (h)] In an English class that is centered on language activities for the purpose of communication, “What should I have the students do for homework? Will sometimes be a problem. The more the class is centered on language activities in which students collaborate with their peers, the more students do not know what to do when they are alone studying at home. The principle is to do things in class that can only be done in class, and to let students do things at home that they can do on their own. It would be appropriate to have the students do dictogloss as “pseudo-communication,” in which they work with their peers to solve problems in class, and to have them do things they can do alone at home, such as listen to the audio again or copy and read the original text aloud.

3 Why is Dictogloss Effective?

The author’s first encounter with dictogloss was in 2006. A teacher came to observe my class. After observing the class, the teacher asked the author, “You conducted dictation in today’s class. What was its purpose? What kind of skills did your students gain?” The question was asked directly to the author. I am ashamed to admit, however, that I was unable to answer the straightforward questions, and flinched, because I had only thought of dictation in general terms as useful for improving English skills. At the same time as feeling frustrated at not being able to answer the questions, the author felt the need to reconsider the purposes and effects of each of the activities in everyday classes. This is what first led me to research and verify why I was trying to incorporate dictation into that part of the class. The author started studying what effects dictation has, and what kind of skills the students gain, leading to the study of dictogloss. As known, dictation involves listening to English and transcribing what is heard literally. What remains is fragmentary textual information in place of the audio that has already been played and lost as information. The author wondered what kind of ability would be needed to complete it as an English sentence in dictation. While researching this question, the author came across the book Grammar Dictation (Oxford University Press) written by Wajnryb (1990). It was then that the author first learned that this research led to an activity called dictogloss. Then I noticed that taking notes of necessary information using audio as input will be used when restoring it later (sometimes in our mind) in our daily lives. For example, taking notes after listening to a class or lecture, reviewing them later or telling them to others, or taking notes while talking on the phone and then recalling the content later. I realized that this is an action that we do naturally in our daily lives.

The author had a lot of questions; Do the levels of difficulties and speed of input speech will change the dictation performance as output? Does effective note-taking skill have the relationship with learners’ English ability? If learners can take good notes in their native language (Japanese), can they also take good notes in English?

Dictation and dictogloss are the same up to the point of “listening” to English, but their purposes (aims) and methods are quite different. Dictogloss is a method of practicing for output, in which the learner “reconstructs” the original English text based on the notes and their memory, using the learner’s world knowledge, etc., while dictation is generally to write what learners hear accurately as possible. Dictogloss is a method of practice putting emphasis on output, and on an autonomous learning policy. It is also an activity that emphasizes noticing (Muranoi, 2006, p. 11), which is said to be important in Second Language Acquisition (SLA), through discussion with peers and comparison and analysis of the reconstructed text with the original text. It is also called pseudo-communication because we naturally do it in our daily life, such as taking notes after listening to a class or lecture and reviewing them later or taking notes while talking on the phone and recalling the content later.

Jacobs & Small (2003) describe dictogloss as an activity that integrates all four skills (p. 2): listening (listening to the teacher read a text), speaking (discussing with group members the restoration of the English text in the target language), reading (listening, taking notes, restoring the text as a group, then reading the original text, etc.), and writing (restoring the text with the target grammar).

Dictogloss is an activity that starts with listening and leads to speaking, writing, and reading. It is expected to develop into an integrated language activity, in which students speak and write (in the target language) based on the information they have heard, and then read the written and original English texts. This is in line with the crucial point in the Course of Study that “integrated language activities are taught comprehensively through language activities in each of the five domains (listening, reading, speaking (exchange), speaking (presentation), and writing as well as through integrated activities that link multiple domains. Dictogloss corresponds to the integration of multiple skills: listening using top-down processing and speaking and writing using the information obtained from listening and bottom-up processing. The students are then able to speak based on the information they have heard and write based on the information they have heard.

3.1 Experiment 1

Now, let us look at some laboratory experiments on the effectiveness of dictogloss. An experiment was conducted with eighty first grade students at a public senior high School in Ishikawa Prefecture. The participants were classified into two groups: Group A and Group B. The students who practice dictogloss regularly in classes were classified in Group A. On the other hand, the students who do not practice it at all were classified in Group B. Oner data was excluded from the analysis because one participant was absent in the post test. Table 1 shows the procedure of this experiment. The participants in Group A practiced dictogloss twenty times during six months and then took post-test. On the other hand, the participants in Group B did not practice dictogloss and just took listening practice in a normal way, and then took post-test. Time spent on study was adjusted so that the two groups would be the same. Step-up listening (STEP Eiken Kyokai) was used in this experiment. This material has ten questions (from No.1 to No.10) in each practice. The level of this material is equivalent as STEP Eiken grade Pre-2 test.

Table 1

Procedure of This Experiment

| Listening pre-test | → | Listening practice (20 times) | → | Listening post-test (6 months later) |

The result

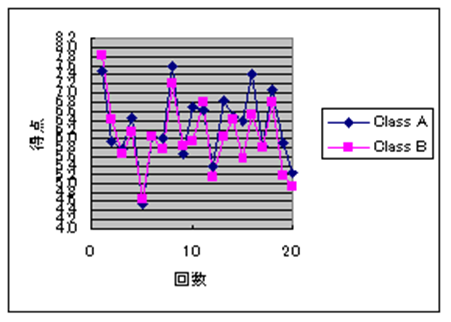

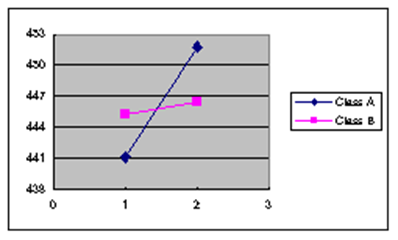

Figure 1 and Table 2 show the result of listening practice. Group B was superior to Group A in terms of the mean score when this practice had started. As the practice proceeded, Group A sometimes, especially after No.10, exceeded Group B. Practice around from 10th was the time when students got accustomed to Dictogloss and they started to write the complicated structures. What is more, Figure 2 shows that there are obvious differences between the two mean scores. The mean score in Group A has grown by 10.7 (9.8% up) and it has statistically significant difference. On the other hand, the average score in Group B has grown only by 1.3.

Figure 1

The Result of Listening Practice (20 times)

Note. Maximum=10.0

Table 2

The Result of Pre- and Post-Test

| Class A | Class B | |||

| M | SD | M | SD | |

| Pre-Test | 441.1 | 57.9 | 445.2 | 46.8 |

| Post-Test | 451.8 | 58.8 | 446.5 | 58.8 |

| t(79) | t = -1.64, p <.05* | t = -0.17, p = .43(ns) | ||

Note. * Shows significant difference

Figure 2

The Differences of Average Score in the Post-Test

Note. Maximum = 640

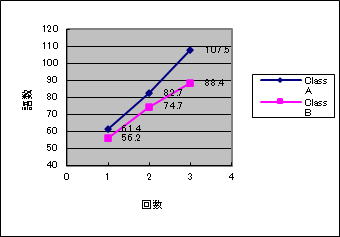

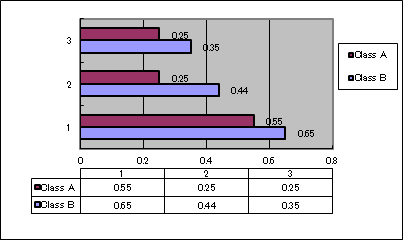

Table 3, Figures 3, and 4 show the result of the writing test. The aim of the test is to make sure that dictogloss practice affected learners’ writing ability. The procedure of the writing test was to have students write about a certain topic such as how to improve the environment of the station where you use every day in 20 minutes. As Figure 3 indicates, students came to be able to write more and more words as the dictogloss practice went on. That is to say, they learned to write a large sum of sentences in English in limited time. Furthermore, Table 3 and Figure 4 indicate that learners came to write correct sentences. They were checking their sentences with each other, and it made them write sentences that had less mistakes.

Table 3

The Result of Writing Test

| Term1(4 months) | Term2(5months) | Term3(6months) | |||||||

| W | G | L | W | G | L | W | G | L | |

| A | 61.4 | 0.76 | 3.41 | 82.7 | 1.87 | 2.05 | 107.5 | 1.22 | 2.73 |

| B | 56.2 | 0.76 | 3.64 | 74.7 | 1.58 | 3.30 | 88.4 | 1.83 | 3.05 |

Note. W = the average words number written within limited time, G = the average number of global errors, L = the average number of local errors.

Figure 3

The Average Words Number Written Within Limited Time (20 minutes)

Figure 4

The Average Number of Global Errors per 10 Words(n = 79)

As mentioned earlier, dictogloss is called as Grammar dictation in a different way (Wajnryb, 1990). This procedure is expected to make learners improve grammatical competence. Here, the errors that learners made were analyzed and a grammar test, which was based on the errors, was conducted. Table 4 and Figure 5 show the result of the grammar test. According to it, we can say that the average score of Group A was 0.7 higher than that of Group B. However, this result did not obtain statistically significant difference. The main reason for it is, it seemed that learners were not able to grab the grammatical points, only if the grammatical points appeared once or twice in practice. This result agrees with previous study. Yamamoto (2005) revealed that only dictogloss instruction was not enough for leaners to acquire the grammatical concept. It suggests that in addition to implicit chances to touch on the grammar points in dictogloss, explicit explanations are sometimes necessary.

Table 4

The Result of Grammar Test

| Class A | Class B | ||||

| t | p | ||||

| M | SD | M | SD | 0.68 | .24(ns) |

| 20.5 | 4.66 | 19.8 | 3.80 | ||

Note. Total score of this grammar test is 78

Figure 5

The Result of Grammar Test (n = 80)

3.2 Experiment 2

Let us take another experiment that study among English ability, note-taking ability and dictogloss performance. In this experiment, 102 Japanese high school students participated. They were first-year students aged between fifteen and sixteen years old. All the participants were native speakers of Japanese. Their English proficiency was basic level (STEP EIKEN test Grade 3 to Pre-2 level). The data of twelve students were excluded from the analysis, because they did not complete the tasks.

The result in Table 5 shows that there is a correlation between English ability and note-taking ability (r =.298), English ability and dictogloss performance (r =.346) and note-taking ability and dictogloss performance (r =.436). When English proficiency is further subdivided into three skills (L/W/R), Table 5 shows that the correlation between L and R is particularly strong. Table 6 shows that the results of multiple regression analysis indicate that high L and R skills also support the success of the dictogloss.

Table 5

The Result Between Learner’s Proficiency and Dictogloss(n = 86)

| Dictogloss | ||

| Listening | .587** | |

| Writing | .179 | |

| Reading | .571** | |

Note. ** p < .01, * p < .05

Table 6

The Results of Multiple Regression Analysis

| Dictogloss | ||

| Listening | .404** | |

| Writing | .058 | |

| Reading | .372** | |

| R2 | .460** | |

4 Summary

An English class without communication is like a physical education (P.E.) class without any body movement. The focus of English classes should be on the learners’ use of English and on communication. However, communication cannot happen with nothing. Starting with pseudo-communication activities such as dictogloss, we hope that the skills developed through this approach will be used in real communication. Dictogloss has the potential to make learners aware and develop their language skills on their own. The process of learners taking notes of what they hear and collaborating with their peers to recover the original English sentences is filled with the rational benefits of second language acquisition. In Japan, Dictogloss practices are already being implemented for junior high school through university students. However, the practice is still very limited, and we hope to see it incorporated in more classes. The effectiveness of dictogloss will vary depending on the speed of listening, how the students are paired or grouped, and the difficulty level of the materials used. We are eagerly awaiting your reports on how you have implemented dictogloss in your daily classes and how you have found it effective!

References

Jacobs, G., & Small, J. (2003). Combining dictogloss and cooperative learning to promote language learning. The Reading Matrix, 3, 1-15.

Maeda, M. (2008). Dictogloss wo mochiita lisuningu noryoku wo nobasu shido – ginokan no togo wo shiya ni irete [The instruction of listening comprehension with dictogloss]. STEP BULLETIN, 20, 149-165.

Maeda, M. (2012). Koko eigo jyugyou ha eigode ha dokomade? [How much should teachers use English in high school English communication lessons?]. Hokkoku Shinbunsha.

Maeda, M. (2018). The potential advantage of dictogloss as an assessment tool for EFL learners’ proficiency. Annual Review of English Language Education in Japan (ARELE), 29, 33-48.

Maeda, M. (2018). Dictogloss wo toriireta eigoryoku wo nobasu gakushuho shidoho [Learning and teaching method by dictogloss to improve EFL learners’ English ability]. Kaitakusha.

Muranoi, H. (2006). Dainigengoshutokukenkyu kara mita kokatekina eigo gakushu shidoho [Second-language acquisition research and second-language learning and teaching]. Taishukan Shoten.

Wajnryb, R. (1990). Grammar Dictation. Oxford University Press.

Yamamoto, K. (2005). The role of dictogloss in developing Japanese EFL learners’ proficiency. BA thesis, Tohoku Gakuin University.